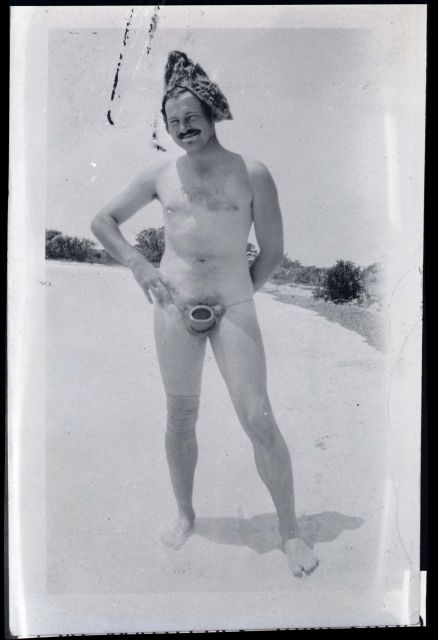

Socket Photograph courtesy of the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana

There are two known original copies of the Socket Photo. The one most studied is at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, donated by the wife of Ernest's close friend Bill Smith. It's possible this connection to Smith is what led Hotchner to presume that the photograph had been taken on the Riviera. He likely knew—as we do, thanks to Brewster Chamberlin's The Hemingway Log—that Smith and Hemingway purchased fishing licenses in nearby Pamplona in late 1925 (Chamberlin 67).

The second known copy came into the possession of Hemingway's one-time friend and cohabitant in Paris, Max Eastman. It is from this copy we get the "true gen" of the photograph's origin.

Hemingway's Socket Photo was taken in 1928 on a beach in the Marquesas Keys, not the Riviera, by friend and painter Waldo Peirce (who created the iconic "Kid Balzac" painting of Ernest) during a Hemingway chartered fishing trip, led by Capt. Eddie "Bra" Saunders, out toward Florida's last stretch of Keys some 70-miles farther west of Key West—the Dry Tortugas. Peirce was quite the shutterbug and captured Ernest in this delightful moment of goofing around. The reason Bill Smith also had a copy of the photograph is that he too was on the fishing trip, as was Hemingway's brother-in-law Paul "Max" Pfeiffer.

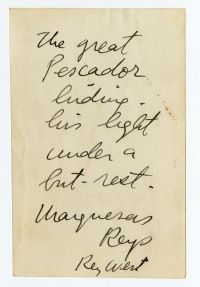

Photograph of the inscription on the back of the Socket Photo, courtesy of the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana

Sharon Hamilton and I examined the inscription, which reads: "The great pescador hiding his light under a but-rest [sic]. Marquesas Keys. Key West." I knew that "pescador" means "fisherman." But it was Sharon who realized that the line is riffing on a Christian adage that originated from the Biblical parable of the lamp under a bushel (Matthew 5:14–15, Mark 4:21–25 and Luke 8:16–18)—that one should not hide his light under a bushel. Thus, we have the joke of EH, the great fisherman, hiding "his light" under the "butt-rest" of his fishing socket.

When Eastman was writing his 1964 book Love and Revolution: My Journey Through an Epoch, Peirce sent him the Socket Photo. By this time Hemingway was dead and the famous fistfight between him and Eastman in the office of Max Perkins was old news. But there has remained the lingering thought, whether true or not, that Eastman despised Hemingway after the fight and was always on the lookout for a way to make Ernest look a fool. A photo of a nearly naked Hemingway—in some sort of silly hat, and pubic hair tufting out over the top of God-knows-what gadget—might offer the chance to do so.

In his book, Eastman wrote: "Among the many amusing sequels of that much laughed-at episode,[sic] was...a picture Waldo Peirce sent me of Ernest on the beach at Marquesas Key when he was not by one half so fur-bearing...." (Eastman 592). He then included the Socket Photo amid a section of photographic inserts (Eastman vix).

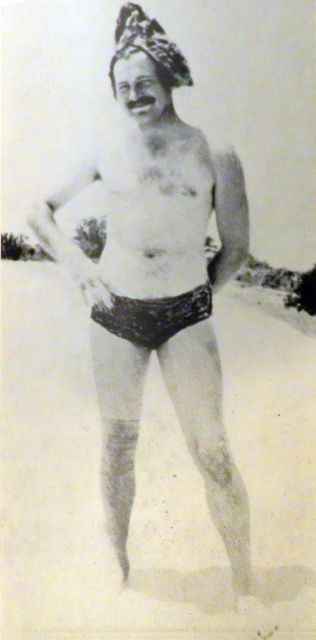

Apparently the book's publisher found the photograph too provocative for 1964 sensibilities, and in the final published version a pair of swim trunks was drawn in with ink across the offending area.

Edited Socket Photo as published in Max Eastman's 1964 book, courtesy of Penguin/Random House

No matter which version of the photo you find, whether in its original glory or with added swimwear, there are two truly remarkable things for us to notice. The first is obvious: it's a photo that genuinely captures Hemingway's deep sense of humor. The other, though, is easily overlooked. Take notice of Hemingway's leg and you will find that, nearly a decade later, he is still bandaging his knee to conceal his war wounds. For a man who abhorred censorship of all kinds and apparently had no problem posing nearly naked on a beach in the middle of nowhere, it's almost as if Hemingway were censoring his own body to hide away what he himself perceived as being obscene. It makes one wonder what he would have thought about the publishers of Eastman's book and their own bit of bizarre censorship. In my mind, Hemingway probably would have just laughed at the silliness of it all.

Works Cited

Chamberlin, Brewster. The Hemingway Log. Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2015.

Eastman, Max. Love and Revolution: My Journey Through an Epoch. New York: Random House, 1964.

John Hargrove is a Michigan-based writer and Hemingway researcher; he is also the founder of "Ernest Hemingway: The True Gen," an online community of Hemingway researchers and aficionados hosted on social media.