--Sir Walter Scott1

When I teach “Indian Camp,” I ask my freshmen students if they think Dr. Adams is a racist. Perhaps because of the increased racial sensitivity resulting from the Black Lives Matter movement, most students are quick to respond negatively to the doctor’s “Her screams are not important. I don’t hear them because they’re not important.” Many read him, almost reflexively, as a racist; only a few see him as a medical professional who concentrates on the obstetrical matter on hand. Those who condemn him ignore the fact that he volunteered to come to the Indian camp to help deliver the Indian woman’s baby, even though he had no medical instruments or anesthesia, making himself responsible for her life and that of her child. His refusal to touch the blanket is not white privilege or daintiness, but medically based: he doesn’t have multiple sterile gloves with which to touch a dirty blanket and then operate. All of these circumstances support a reading of Dr. Adams’ actions as not being driven by racial bias, especially considering that the doctor's brother calls the woman a “squaw bitch,” while Dr. Adams three times refers to her as a lady as he works to save her life and that of her child.

And in calling her a lady, he treats her as a lady, using silk in her caesarian sutures: the leader he would have used would have been silkgut, the gut of the silkworm larva, bombyx mori, before it extruded silk filament. After World War II nylon, dacron, and other artificial filaments replaced the natural fibers that had been used prior to the war. Historically, in the 18th and 19th centuries, fishing lines were made of twisted horse hair, silk thread, or both together. Young Nick Adams may have learned fishing with cheap cotton line, then graduated to linen lines; both absorbed water, grew heavy, and, being vegetable fiber, had to be treated so as not to absorb water, but still had to be dried, or the lines would rot. Braided silk thread was preferred as a line, oiled or enameled so as not to absorb water and so as to glide more easily off the reel and through the guides, and is probably what Dr. Adams and his brother used to fish. But it is not enameled silk line that he uses to sew up her incisions, but silkgut, which the body will absorb.

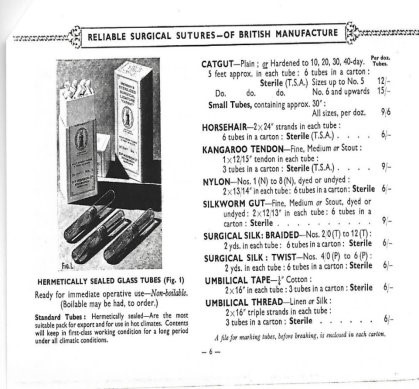

The leader, the several feet between the end of the line and the hook, was of a tougher material to withstand a fish’s jaws or plants or roots it might snag on; it was also less visible in the water to fish than white silk thread. Although described as gut leader, it was not what we used to call catgut—sheep’s intestines, used on stringed instruments and in pre-war tennis rackets—but silkworm gut. The silkworms, for most imports to the U.S. through British dealers, were raised in Murcia, Spain. The silkworm sacks were extracted from pickled silkworms immediately before they would have produced silk filament. These sacks were cleaned and stretched to between 10-14 inches and sold in hanks for fishermen to knot together, using their favorite knots, to make leaders.2 Silkgut was also used in the tying of artificial flies.3 As almost pure collagen, especially if well cleaned, silkgut is absorbable by the body and has been distributed for surgical use as late as 1942. The following picture, featuring silkworm gut in the center, is from, G.F. Merson’s Medical Supplies catalog from 1942, before Merson’s was bought out by Johnson and Johnson in 1947 and renamed Ethicon.

Fishermen in Hemingway’s day, when “Indian Camp” was first published in 1925, knew that gut leader meant silkgut. The author, averse to footnotes, never sought to correct it, especially since he stopped fresh-water fishing before the Second World War. His fishing gear was lost when Railway Express lost a trunk of it en route to Sun Valley in 1940; it would have included silkgut leaders in pads soaked in water or glycerin to keep them supple. Jack Hemingway says he remembers his father fishing in streams or rivers only once thereafter.4 Instead, he hunted in Idaho and Wyoming, and deep-sea fished off Cuba, where leaders were wire, not silkgut, and thus no further mention of fresh-water fishing tackle in his works. We, who grew up in the age of synthetic fishing lines and leaders, pass over “gut leader” without pause, but those with knowledge of fishing practices in the early 20th century, know that Dr. Adams’ gut leaders were made of silk, and so were the Indian woman’s sutures, silken ties, for a lady.

Notes

1 Sir Walter Scott, “The Lay of the Last Minstrel,” https://www.theotherpages.org/poems/minstrel.html

2 “Gut leader is sold in hanks containing an average twenty-five strands running from ten to fourteen inches in length” (65). “[I]t takes from six to eight strands, depending on their length, to produce a leader six feet long” (68). Larry St. John, Practical Fly Fishing, Macmillan, 1920.

Cf. John Harrington Keene, The Boy’s Own Guide to Fishing, Lee and Shepard, 1894, p. 22.

3 William Mills & Sons Catalog, Great Fishing Tackle Catalogs, Ed by Samuel Melnor and Hermann Kessler, Crown, 1972, 99; see also p. 101.

4 Keith McCafferty, Preface, Cold-Hearted River, Viking, 2017. The one subsequent time was probably 1946 when Mary was recuperating from the surgery following her ectopic pregnancy, and Hemingway took breaks to fish with her doctor or later at Sun Valley with his sons. Cf Reynolds, 149.

Bibliography

Hemingway, Ernest. The Sun Also Rises & Other Writings, ed. Robert W. Trogdon, Library of America, 2020.

Keene, John Harrington. Practical Fly Fishing, Macmillan, 1920.

Martin, Lothar H.H. “The History of Silkworm Gut,” The American Fly Fisher, 17:3 (Fall 1991), 3-7.

McCafferty, Keith. Cold-Hearted River, Viking, 2017.

Merson’s Catalog, 1942, courtesy of Ethicon.

Reynolds, Michael. Hemingway: The Final Years, Norton, 1999.

Scott, Sir Walter. "The Lay of the Last Minstrel." www.theotherpages.org/poems/minstrel.html, 2020.

St. John, Larry. Practical Fly Fishing. Macmillan, 1920.

The late Peter Hays was a founding member of the Hemingway Society and served on its board for many years. Author of dozens of articles and books on Hemingway, Peter wrote widely on American literature and served as well on the boards of the Fitzgerald and Wharton societies. Myrna, his wife of nearly 60 years, has worked to bring his final projects to publication.