KEY WEST - Speak, memory.

In 1990, I became the literary intern to controversial Beatles biographer Geoffrey Giuliano. He lived in an 18-room 1860s Lockport, New York, mansion on the Erie Canal, less than a quarter mile from my college apartment.

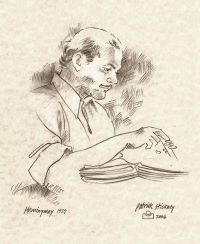

I was reading Carlos Baker’s biography of Hemingway at the time. I carried the book with me everywhere, as other hopeful young writers did with On the Road and The Catcher in the Rye.

I started work for Giuliano (who starred recently as the masked lion on Netflix’s blockbuster Squid Game) in August, skipping my senior year as an English Literature student at the State University of New York at Buffalo (UB). It was at UB that I was first introduced to In Our Time and The Sun Also Rises.

One of my UB literature professors, Mark Schechner (b. 1940, d. 2015) an internationally respected James Joyce scholar and book reviewer, looked at Hemingway’s early writings as partially “experimental.”

Schechner asked his students why the characters in The Sun Also Rises are drawn to churches—“Why do they keep going in and out of them? What or whom are they looking for? Is the exercise a balance to the sex, drinking and loss of self in Spain? Or does it go deeper?”

I had my ideas. Hemingway aficionados have theirs. Something related that appealed to me was how The Sun Also Rises took the characters passionately “on the road” as Kerouac did years later. I developed a longing for journeying, notebook in hand, to see the magic and doom of those I’d read about.

At Giuliano’s, I proofread galleys of Blackbird, his developing biography of Paul McCartney, babysat his crazy children, and searched with purpose through his multi-room museum of multimedia Beatle memorabilia for dates, places, and lost interviews.

The days at Giuliano's place were meditative, the Moody Blues, The Who, and Hendrix on the house melody mix as if we lived in a permanent Woodstock, 1969. Rock stars, photographers, reporters, and the local police were at the house daily—I was never sure why.

“The author?” I’d say at the massive entry’s ornate and aqua windowed double doors. “He’s unavailable now. I’ll have him ring you later.” I was the ideal intern and future investigative journalist.

The winds of a crisp fall, the rains, and the chameleon leaves turned summer’s passions to nostalgia, recalling a heartbroken past like McCartney’s “Once Upon a Long Ago.” I felt it. And I knew Giuliano, 15 or so years my senior, felt the same when I heard “Mull of Kintyre” echoing through the hallways, like cries from another century.

The tourist boats along the Erie Canal had ceased for the season and everything was broken and dying. The concept of death, and our existential connection, teased me as I sifted through Beatles research for Giuliano. John Lennon had been murdered a decade earlier; the Beatles were no more. Then on my writing desk was Baker’s Hemingway, a man who’d taken his own life on July 2, 1961.

I overthought my role, common for folks like me, and got a chill when I realized I was chasing my dream, but I was also working with ghosts, images, lives ended, songs from the past, memories, nostalgia, celebrity obsessions, and books and stories that began and ended in tragedy.

The fiction I loved explored the boundaries, the biographies I read were all too human—the Beatles sought enlightenment the way Hemingway sought distraction from reality. And, I thought, why are we, as appreciators of these arts, filled with so much longing for pasts that existed, sometimes, years before we were even born?

So, I had an idea, as a man of 22 might have, to save our creative souls from another morose Buffalo area winter blizzard season.

“Geoffrey?” I said at the door of his writing room. “Writers can work anywhere,” a thought I’d borrowed from my second or third reading of The World According to Garp.

“Why don’t we pack up and do a working vacation away from here?”

I suggested Florida because I knew Geoffrey’s wife’s parents lived in Tampa. I also knew about Ernest Hemingway’s Key West house, the place I’d read about in Baker’s celebrated biography of America’s longtime literary tough guy.

I’ll admit, as I read more Hemingway, he became my rock star. So, I wondered if we (Geoffrey and I), as musical journalists, could visit that sacred place, where I might find answers to my questions about chasing ghosts.

When I'd made my request, it was as if a supernova, an otherworldly enlightenment from a literary cherub, had descended upon Giuliano’s concerned grace.

“Indeed, Brandon boy,” he said, grinning, a moment on the mind. “Let’s go there.”

To be continued . . .

Brandon M. Stickney is a biographer, historical writer, and documentarian who has appeared on A&E, NPR, the History Channel, and the Travel Channel's Mysteries in the Museum. He has two cats: Gordon Lightfoot and Little Bones.