If you want to know about the day-to-day activities of the so-called Lost Generation in Paris—what ships they sailed in on, what hotels they stayed in, who dined with whom--there’s no source more comprehensive than the Chicago Tribune’s Paris edition. The Paris Tribune was a daily competitor to the Paris Herald from 1919-1934 (when the papers merged they formed the long-lived International Herald Tribune), and made a point of reporting on the Left Bank’s artists and intellectuals alongside Paris’ many other Americans.

The problem with the Paris Tribune is what periodicals scholar Patrick Collier has termed a “problem of plenitude”—during the Tribune’s fifteen-year run it published over 5,000 daily editions, most at least 8 pages long. Less than a decade ago, when I began looking at the paper, the only way for most researchers to access it was through a poorly scanned and poorly catalogued collection of circulating microfilm. The paper’s fifteen year run spanned more than sixty reels, and the libraries to which it belonged doled out four to six reels at a time via Interlibrary Loan. As each batch came in, I spent long days and nights in my campus library skimming as quickly as I could and hoping something exciting would jump out, well aware that in my desire to cover as much ground as possible in search of a big discovery, I was likely missing all the small ones.

Then, in 2018, a minor miracle occurred: the French Bibliotheque nationale de France digitized the paper’s entire daily run, made it publicly available and searchable. It was a game changer. There are reasons to be cautious about the transition from paper to text-searchable archives—as Lara Putnam wrote in 2016, we risk losing both the serendipitous and the contextual in our research practices—but for biographical scholarship it’s hard to overstate its possibilities.

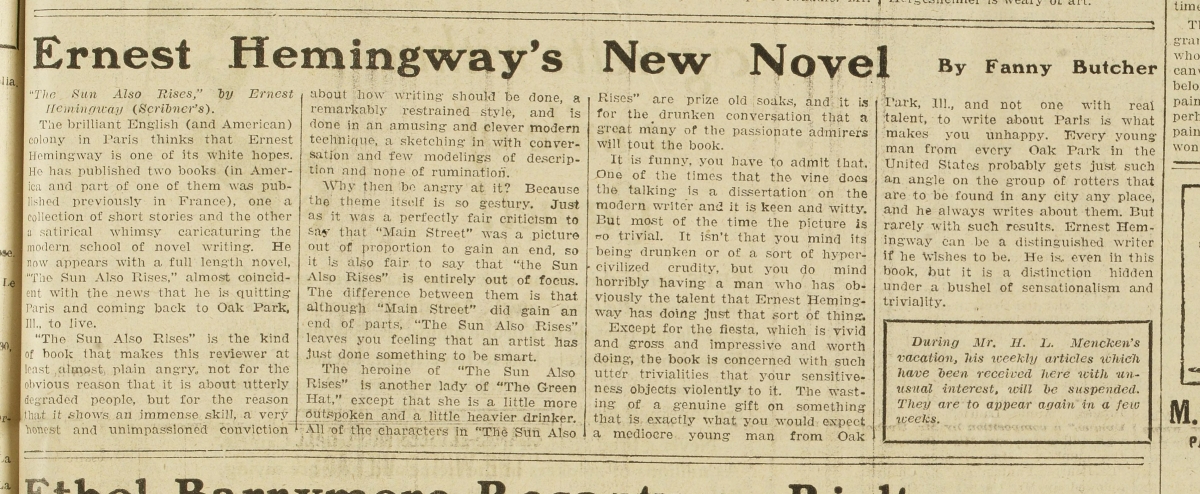

It means being able to say what year the paper began to treat Hemingway’s daily actions as newsworthy (1926—the year the Tribune reported “it is now the right thing to mention [Hemingway’s] name casually, as if one had read his stories, and the cult is being founded”; to compare how often Hemingway was mentioned in the paper that year (16 times) versus his friend John Dos Passos (four), or Gertrude Stein (seven); or stumble upon Left Bank documenter Wambly Bald’s description of Hemingway as having shoulders “like Army trunks.”

In 2005, Patrick Leary worried that those periodicals that weren’t digitized would be relegated to an “offline penumbra…that increasingly remote and unvisited shadowland into which even quite important texts fall if they cannot be explored…by any electronic means.” Now that the Paris Tribune’s archive is available to all of us, it promises to illuminate as-yet unexplored corners of the Lost Generation’s interwar lives.

Nissa Ren Cannon is a Lecturer in the Program in Writing and Rhetoric at Stanford University. Her research focuses on the literary, print, and material culture of transatlantic interwar expatriation.