Writing from Toronto to his friend Gertrude Stein in Paris, in early November 1923, just weeks after the birth of his first child John "Bumby" Hemingway, Ernest Hemingway poked fun at a book called The Canadian Mother's Book. The book had been given to Hadley, for free, by the Canadian government as part of a program to provide parenting tips to new families. It quickly became a source of amusement in the Hemingway household. In his letter to Stein, Ernest joked that when it came time in the morning for Hadley to nurse Bumby, he would say, "Daddy will have to push the Canadian Mother out of bed. Won't you Daddy?"1

When I encountered this letter, in The Letters of Ernest Hemingway - Volume 2, it occurred to me that since the "Mother's Book" had been published by the Canadian Department of Health, a copy must be preserved at the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) in the capital city of Ottawa, where I live. I realized I could go and look at a copy of the book that Ernest and Hadley had received to help them become new parents, and that Ernest had mocked. Both were clearly familiar with the contents of this book, as Ernest knew enough about its content and style to joke about it with Hadley and to be able to write to Gertrude that the book “is full of phrases like ‘Daddy will do it. Won’t you Daddy?’”

A quick look at the LAC's online catalogue revealed they held copies dating from its first publication in 1921 until the final in 1938,2 including the edition from 1923— the one supplied to Hadley. I put in my request to see the 1923 edition and made arrangements to go downtown the next day.

When I arrived at the LAC, the object I had requested rested on a wooden shelf. I noted as I advanced that appropriately—considering its association with babies—it appeared to be wrapped in a kind of protective swaddling. This book that the librarians had left on the shelf for me could not initially be seen at all, covered as it was in a protective, white, cardboard case tied gently closed with a fabric ribbon. After moving the object onto one of the long wooden tables in the research area, I pulled on the ribbon.

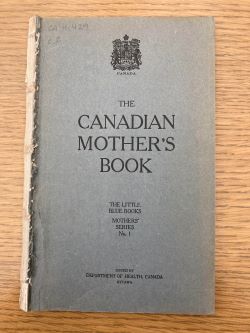

It turned out that the book inside required such a protective case because it no longer had a back cover. The light blue of the front cover remained, though, and announced that I was looking at a copy of The Canadian Mother’s Book, a thin, pamphlet-like publication of 136 pages provided to the country’s expectant mothers.

Opening the soft cover, I scanned the table of contents. Chapter titles like “Maternal Nursing and Care” and “The Baby’s Habits, Health and Nutrition,” read much like what one would find in the What to Expect When You're Expecting type of advice book still published today. As I began to read, though, I was surprised to find how much of the advice given in those chapters from a century ago outlined things that still make sense for pregnant women today. For example, regular exercise was advised, noting that it should not be too strenuous, and that one should stay well hydrated. The section on diet indicated that regularly consuming protein was a good idea, and eating meals with lots of vegetables was encouraged.

Beyond the continuing relevance of such practical advice, there were other passages that ended up startling me with their unexpected modernity—especially the degree to which the book promoted female autonomy. Under certain circumstances, to protect their own health and that of their babies, the book encouraged women to evaluate, even to challenge, their healthcare providers. For example, the book included advice that if a doctor or nurse challenged the mother’s wish to breastfeed her baby, she should ask if there were a specific medical reason not to do so; if the doctor could not provide one, the book urged the new mother not to listen, and to breastfeed the baby anyway. In this way, this little book Hadley once read embodied a kind of feminist activism. The book also insisted that the baby’s father play an important role in supporting his pregnant spouse, something Hemingway likely resented, and would soon be mocking in letters to his friends.

Works Cited

Hemingway, Ernest. Letter to Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, 9 November 1923 and [c. mid-December 1923], The Letters of Ernest Hemingway 1923-1925. Volume 2, Edited by Sandra Spanier, Albert J. Defazio, and Robert W. Trogdon (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2013).

MacMurchy, Helen. The Canadian Mother’s Book. Dominion of Canada Department of Health (Ottawa: F. A. Acland, 1923). [See this link for a full text scan of the 1921 edition: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=ien.35558005446493&seq=5]

1 Ernest Hemingway, letter to Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, 9 November 1923 and [c. mid-December 1923], The Letters of Ernest Hemingway 1923-1925. Volume 2, Edited by Sandra Spanier, Albert J. Defazio, and Robert W. Trogdon (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2013), 90.

2 The Canadian Mother's Book was replaced in 1940 by a new series titled The Canadian Mother and Child.

Sharon Hamilton is a member of the Hemingway Society Board. She has blogged previously for the Hemingway Society about Hemingway and Hadley’s Chicago Apartment, Hemingway’s New Orleans, and the baseball ticket stub the author took with him to the front in World War I. In October 2023, she presented a webinar on "Hemingway in Toronto" to members of the Hemingway Society.