The index of Brasch and Sigman’s endlessly fascinating inventory of Hemingway’s personal library lists two books under the entry, “Automobile,” the first under the subheading of “industry” and the second under the subheading of “racing.”

The first is The Insolent Chariots (#3506) by John Keats. Hyphens replace the name in the listing, suggesting that he is also the author of the previous selection: The Poetical Works of John Keats (#3505). He is not. The Insolent Chariots is a sociological and economic analysis of the automobile in American society. The second listing is Adventure on Wheels: The Autobiography of a Road Racing Champion (# 2214) by John Fitch with William W. Nolan.

This would seem to indicate a minimal interest on Hemingway’s part regarding the topics of automobiles and racing. The listings, however, include three other non-indexed volumes of interest on these topics. Ken W. Purdy’s The Kings of the Road (#5390) covers what might be called the romance of the automobile. The other two, John Bentley’s The Faster They Go (#539) and Hans Ruesch’s The Racer (#5721), are both novels about auto racing. These five volumes are of varying degrees of interest and relevance for the Hemingway reader, scholar, and biographer. As titles are not always completely revealing of the contents of books, I cannot claim that there are no other volumes on these topics in the inventory.

Purdy’s Kings (1952) and Reusch’s Racer (1953) were both published before the period that Hemingway worked on Under Kilimanjaro / True at First Light (Fall of 1954 to Spring of 1956), in which he makes two of the rare motor racing references in his works. He refers to “an open motorcar [that] pulled up to a dirt-track racing stop alongside the tent” (UK 53/TAFL 52). Later he employs a racing metaphor: “Ngui drank it like a racing driver quenching his thirst at a pit stop” (UK 430/TAFL 304). These references suggest an awareness of different types of racing as there are no pit stops in dirt-track racing.

The Fitch volume, because it was not published until 1959 and not obtained until 1961, sparked the least interest for me, not to mention the fact that it was the rarest and most expensive. The book might even have arrived after Hemingway’s death. The only conclusion I could initially take from this book’s appearance in the inventory regarded Hemingway’s preferences in choosing books. Fitch, like Bentley and Ruesch, was an accomplished racing driver. Naturally, it comes as no surprise that Hemingway might consider that books on racing by actual racing drivers would be the most authentic ones and that such a consideration would be reflected in his book choices. However, upon (finally) obtaining a copy and reading it, I saw new connections.

Although Fitch (1917-2012) wrote this book as an autobiography, he had much of his life left to live, and his accomplishments in and out of racing were many and notable in the decades that followed. Prior to World War II, he attempted to enlist in the Royal Air Force (RAF) but found they had sufficient numbers of pilots. He returned to the US in 1939, took up residence in Florida, bought a schooner with inheritance money, and volunteered with the Coast Guard “to back its antisubmarine patrols.” If Hemingway had known this about Fitch, he might have felt a kinship and ordered Fitch’s book. Fitch eventually became a successful fighter pilot, surviving being shot down and captured near the end of the war. This too might have sparked Hemingway’s admiration enough to obtain a copy of Fitch’s book. After the war Fitch pursued a successful career as a road racer for hire, competing successfully in Europe and North America at the top levels and establishing a reputation of international note. Parts of the book were originally published in periodicals in which Hemingway was also published—True, Esquire, and Atlantic Monthly—which might have brought Fitch’s name to Hemingway’s attention.

The title page of the Bentley’s 1957 volume lists the title as The Faster They Go: A Novel of Motor Racing. The novel is set in the 1950s, beginning at the Carrera Panamericana Mexico (a grueling race on public roads which ran from 1950-1954 and in which Fitch also competed). It is the first-person tale of a driver’s progress up the ladder of the sport from driving underfunded sports cars to competing in Grand Prix racing. The protagonist rescues a top driver from a dangerous situation, gains better rides as a result, and the two eventually become rivals. The novel makes a very odd turn into espionage when the rival driver is detained in East Berlin and the narrator, against his career interests, helps to extricate him so that the two may compete in the climactic race. The racing scenes are vividly described, and there is, against all probability, a reference to someone Hemingway had written about, suggesting that Bentley had read his Hemingway: “You couldn’t hold a woman like that unless you were as daring as Belmonte and as rich as Onassis” (167-68).

Ken W. Purdy (1913-1972) was one of the top automotive journalists of the twentieth century. He was an associate editor of Look and editor of True, both publications that included pieces by Hemingway and Fitch. Purdy was editor of True when in April 1951 it published Hemingway’s The Shot, later collected in Byline: Ernest Hemingway. It would not be surprising if the Hemingway Letters Project should eventually turn up correspondence between Hemingway and Purdy. Purdy too died of suicide by gunshot.

Purdy’s Kings of the Road includes chapters on famous makes—Bugatti, Mercedes, and Dusenberg, for example; famous drivers—Nuvolari; and famous tracks—Indianapolis and Le Mans, thus interpreting the book’s title broadly. The key relevance to Hemingway studies is in the volume’s presentation of the Bugatti, the car of David and Catherine in The Garden of Eden. The Bugatti is a rare car; Ettore Bugatti built less than 10,000 cars during his career. It is quite possible that Hemingway—or any of his contemporaries—could have gone through life without ever even catching a glimpse of a Bugatti. This makes it possible that the Purdy volume and not personal experience was the inspiration for Catherine and David’s ride. Indeed, the frontispiece of Kings of the Road, a striking photograph of a bright red Bugatti 57SC, would arrest the attention of anyone who even opens this volume. David and Catherine’s Bugatti was blue, and indeed racing Bugattis were typically liveried in French racing blue. This actually argues in favor of the classic Type 35 Bugatti (1924-1931), used in both racing and on public roads in its day. This assumes that The Garden of Eden takes place in the 1920s. But if Hemingway’s source on Bugattis was Purdy, then the Type 57SC (1936-1938) emerges, despite its anachronism, as the ride of Catherine and David, at least in Hemingway’s imagination. After a brief introductory opening, Purdy’s entire first content chapter is devoted to the both the man and his cars, including discussion of the high-maintenance nature of the Bugatti, as well as the fanatical devotion of Bugatti owners, suggesting the make as the likely choice for high-maintenance types like Catherine and David. When Marita arrives, it is in an Isotta, which Purdy discusses briefly in a later chapter.

The Type 35 was built from 1925 to 1929 would seem to be the period-correct Bugatti for David and Catherine to have driven. It was highly successful in international racing, and nearly all are liveried in French Racing Blue, as is this one. It could also be driven on public roads, and what looks like a Type 35 used in the 2010 film of The Garden of Eden does indeed have fenders and headlights. However, the image of Catherine and David dressed to the nines in an open roadster (with no convertible top) and a couple of suitcases strapped behind them strains credulity.

The Type 35 was built from 1925 to 1929 would seem to be the period-correct Bugatti for David and Catherine to have driven. It was highly successful in international racing, and nearly all are liveried in French Racing Blue, as is this one. It could also be driven on public roads, and what looks like a Type 35 used in the 2010 film of The Garden of Eden does indeed have fenders and headlights. However, the image of Catherine and David dressed to the nines in an open roadster (with no convertible top) and a couple of suitcases strapped behind them strains credulity.

The Bugatti that Hemingway may well have had in mind when he decoded to place Catherine and David in one may well have been the somewhat more practical but still dramatically dashing Type 57SC. The frontispiece of Purdy’s Kings of the Road is a photo of a striking red with matching wire wheels 57SC very similar in body style to the one depicted here.

The most interesting of these volumes is Hans Ruesch’s 1953 novel The Racer. The novel is about European Grand Prix racing in the 1930s. The Swiss and Italian Ruesch (1913-2007) not only participated in racing, but he was also a Grand Prix winner, even driving for Enzo Ferrari’s Alfa Romeo race team years before Ferrari began building his own cars. After his racing career, he pursued other sports and finally a successful career as a writer. The authenticity of invention based on personal experience would certainly have appealed to Hemingway.

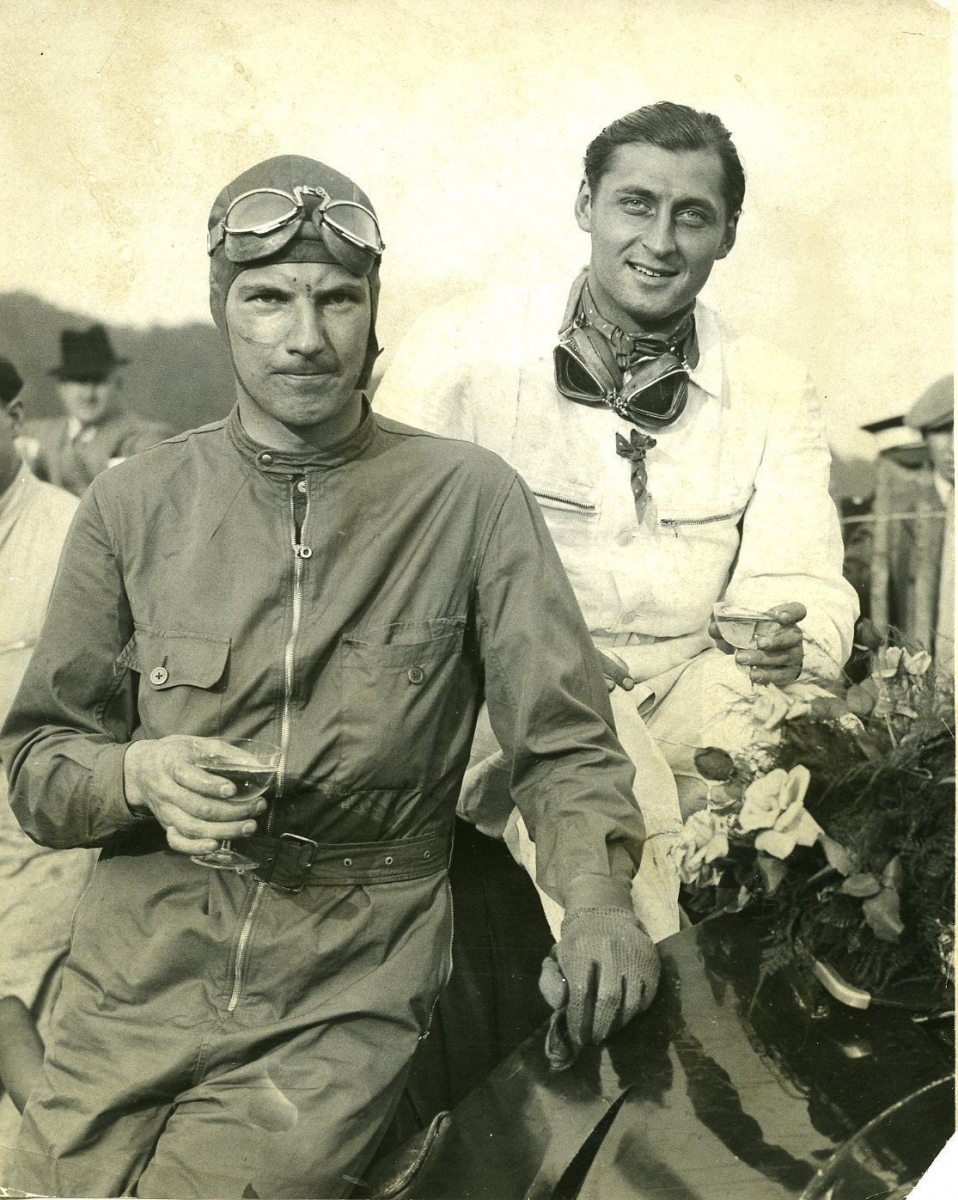

The ruggedly handsome Ruesch (r) on October 3, 1936, the day of his greatest racing triumph, a first-place finish in the Donington Grand Prix, a virtual Grand Prix of Great Britain. He celebrates here with his co-driver, the legendary British Grand Prix ace, Richard Seaman. Their car that day, an ex-Nuvolari, ex-Scuderia Ferrari Alfa-Romeo 8C-35, has survived to command record prices at auctions. The Bonhams auction house promotions included actual footage of both Ruesch and Seaman driving the Alfa at the Donington Grand Prix: https://www.hemmings.com/blog/2013/09/17/alfa-romeo-8c-35-grand-prix-racer-sells-for-record-setting-9-4-million/

The novel was filmed in 1955 as The Racers, starring Kirk Douglas, along with Cesar Romero, Bella Darvi, Gilbert Roland, Lee J. Cobb, and Katy Jurado. John Fitch worked as a technical advisor and stunt driver on the film. Its racing footage made it the definitive auto racing film until decisively superseded by John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix (1966); both films combined groundbreaking racing footage with soapy love plots. Despite Ruesch’s co-authoring the screenplay, the plot of the film is so entirely different from the plot of the novel that even the name of the protagonist is changed (from Erich Lester to Gino Borgesa, portrayed by Douglas). It seems that even Ruesch understood that the ending of the novel was entirely too dark for a Hollywood production. The conflict of both, however, remains the same: the clash between older established drivers and brash younger drivers.

Reusch’s plot works out this conflict within the context of the appalling carnage, visited upon both drivers and spectators, sadly the tragic norm during the 1930s. This is not to say that conditions had improved significantly by the 1950s. Prior to the advent of corporate sponsorship and worldwide television, financial interests—such as promoters, track owners, race teams, and manufacturers—all conspired to perpetuate the fiction that death was an inevitable accompaniment of auto racing. Ruesch’s novel takes place in that atmosphere, as did his own driving career. Erich Lester, a determined and talented young driver, is Ruesch’s protagonist. He succeeds by detaching himself emotionally from the tragedy and death around him, including his own crashes and injuries until he meets the lovely Monica, the only person to whom he opens up. They eventually marry, and Erich climbs to the top of his profession, defeating and replacing his older rivals. The team intrigue and the emotional detachment he maintains in order to defeat the men who are both his mentors and rivals in what amounts to death duels eventually take their toll on his marriage, and Monica leaves him, taking up with Rory O’Hanlon, an up-and-coming driver, in whom Lester sees his younger self.

The novel then begins its dark closing sequence. Determined that he should not appear to have been pushed into retirement by younger drivers, Lester decides to drive in his last season with complete abandon, crushing all competition and going out on top. However, because he cannot beat Rory, this plan fails, and the dejected Lester then plans his own on-track suicide. At the Grand Prix of Italy, he plans to drive off track and crash at the famous (then and now) Lesmo corners of the Monza racetrack, thus achieving what to him seems an honorable exit from a bloody sport. This plan too fails, for when he arrives at Lesmo on the first lap of the race, he sees that another car has already gone off the track at the exact spot where he had intended to crash. It was Rory who had crashed, and Lester goes on to win the race. Hollywood could have gone this far had they decided to follow Ruesch’s original plot, but no further.

Days after the race Rory requests that Lester visit him in the hospital, where he finds Rory permanently paralyzed, drugged, and suffering in excruciating pain. Rory reveals that he sped into the fatal turn because Lester had mentioned before the race that there was oil on the track in that turn, supposing that Lester said it for the sole purpose of taking advantage of other drivers who might slow their pace there. Lester thus feels complicit in Erich’s accident and is vulnerable to Rory’s request that Lester provide him with a handgun with which he can commit suicide. Lester refuses, but on his way out meets Monica. She is devastated by Rory’s condition and her inability to care for him. After consulting with a professor over Rory’s x-rays, Lester returns to Rory’s room with the requested gun, says goodbye to Monica, and drives off into the dark.

A few years after The Racer was published, Hemingway followed the extended competition of two bullfighters: the up-and-coming Antonio Ordóñez and the older established Miguel Dominguin in their famous series of mano-a-mano appearances in bull rings across Spain during the dangerous summer of 1959. The recurring mistake of Hemingway criticism is the kneejerk assumption that the material he developed is exclusively experiential rather than literary or his own invention. If Hemingway had read The Racer, Erich Lester’s conflicts with rivals—both older and younger and at both the beginning and ending of his racing career—might possibly have been in the back of his mind during his writing of The Dangerous Summer.

In addition and also during the 1950s, Hemingway confronted his younger self in writing A Moveable Feast, another parallel with Erich Lester, who confronts his younger self in Rory. For Rory, being unable to race or even to enjoy life, suicide is the only answer he can find. Naturally one wonders whether Hemingway read the novel, one that develops the theme of confronting one’s older as well as one’s younger self, not to mention the themes of suicide and assisted suicide. One also wonders whether Mary might have read it.