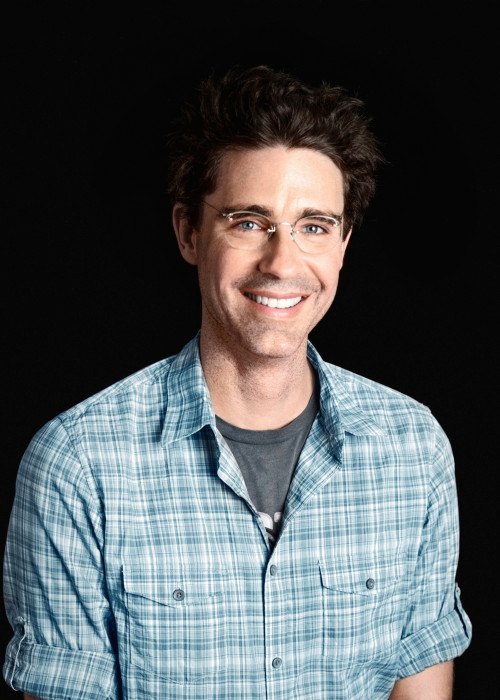

Joshua Ferris, 2008 PEN/Hemingway Award Winner for Then We Came to the End

Q: What was it like growing up in the Midwest?

A: It was tolerable until the divorce. My dad was kind and lenient, my mom strict and exacting. We lived on a uniquely busy road for Danville, Illinois, in a white Victorian with a wrap-around porch under which I dwelled in summer from morning to night in imaginative games. At night, I required my father to pull the blind before I could sleep; I was convinced that exotic animals, two of every kind, paraded down our drive when it got dark, and I was deathly afraid of them peering in at me. This was how Sunday school invaded my dreams. We had neighbors to the right and left, but just beyond, where the town ended, the silos and combine harvesters grew up alongside the cornfields. I loved the dogs, the parks, the parades, the ballgames at dusk, and the plays at the local theater. But then, as I say, divorce struck, the family shattered, and all the shards dispersed, were hoovered up, moved to Florida, etc…

In the Charles Portis novel, The Dog of the South, an old doyenne says to the hero, who has turned the ripe-old age of 36, “All of the pets of your youth are dead.” All the pets of my youth died in my youth, usually under the tires of my father’s Plymouth.

Q: Who inspired you to become a writer at the University of Iowa and UC-Irvine? (Ferris earned his BA from the University of Iowa and his MFA from UC-Irvine):

A: No one. I had teachers and encouragers, and men and women who I admired for the work they did, but only other writers inspired me to be a writer, beginning when I was six with William Steig, whose Sylvester and the Magic Pebble was the first book I can recall enchanting and terrifying me with the mystery of its imagined laws.

Q: Are you still a Hawkeye fan?

A: Was I ever one?

Q: Is working in adverting as hectic as people think? (Ferris worked in the advertising industry in Chicago before becoming a full-time author.)

A: Hectic ... well, that depends. Is business good? Are you at a respectable firm? Is your team ambitious? Is creativity valued? Is it 1999, or 2019? You can throw every last hour and more into the great maw of advertising and still have more to do. What’s worse, at a dull shop, you may have nothing to show for all that hard work but business-reply cards and cut-rate catalogues. What I’d argue, though, is that no matter who you work for, no matter how sparkling the product, you remain handmaiden to commerce and in league with thieves, which can make the going harder.

Q: Are the characters in your debut novel autobiographical?

A: They are in spirit—or even better, in aura—but in name and fact they are completely invented. How I wish I could just pluck a few avatars from the wider world and fashion a novel around them! It’d be a much easier business.

Q: Did you write this award-winning novel right after the dot-com bust, or after you received your MFA from UC-Irvine?

A: I had completed my MFA and had retired my earlier attempts to write it when it came to me almost fully formed one night in a bright little flash that prompted me off the bed toward the desk, where I stayed for the next 14 weeks. It was the effect of some kind of long-pressurized release valve that had begun to build while I was still working in advertising, found some frustrated relief during my time as a student, and then finally got written down only after I stepped out of the office and out of the classroom. That is the most vital and productive part of earning an MFA: becoming a person again.

Q: Do you remember where you were when you received the news about winning the PEN/Hemingway Award?

A: My wife & I had just bought our first car together. It was a 2008 gun-metal grey Subaru Outback. We were living in Brooklyn at the time, parking the car on the street. Some mornings the car was my responsibility, some mornings it was my wife’s.

Well, she sorta forgot about it, often enough that she accumulated roughly twenty parking tickets. These came with other fines and taxes until it was finally towed. We had to retrieve it from Queens. The tow and the impounding fee, together with the outstanding tickets, ran us a total of about two thousand bucks. It was a huge and terrible fine. What my wife remembers best, though, is the man at the tow lot telling us we’d make it as a couple because we were still smiling, as opposed to—I suppose—sharpening our knives behind each other’s backs, as he must have seen a million times.

We were returning to Brooklyn in the Subaru, approaching the toll booth, when my phone lit up with the news. The award came with some cash money, too, enough to make up for what we’d just paid out to the city of New York.

Q: Do you have a favorite Ernest Hemingway story or book?

A: I’m partial to “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” and to the stories in general: “The Killers,” “Hills Like White Elephants,” the Nick Adams stories. But my favorite, of course, to which I return again and again, is his first brilliant elliptical shivering romantic novel, The Sun Also Rises.

Q: Are you working on anything new at the moment?

A: Another novel, this one about my father.