Late in 1952, Wallace Meyer, an editor at Scribner’s, sent out Brown’s typescript for vetting. This was the usual practice; it still is. A negative reading could kill a book. The reaction to Brown’s work was nothing short of overkill. The margins of the typescript were crowded with venomous remarks. Brown’s intelligence, writing, and even his manhood were vilified. Whoever inflicted this assault had to be someone with a violent temper who assumed enormous authority regarding Hemingway.

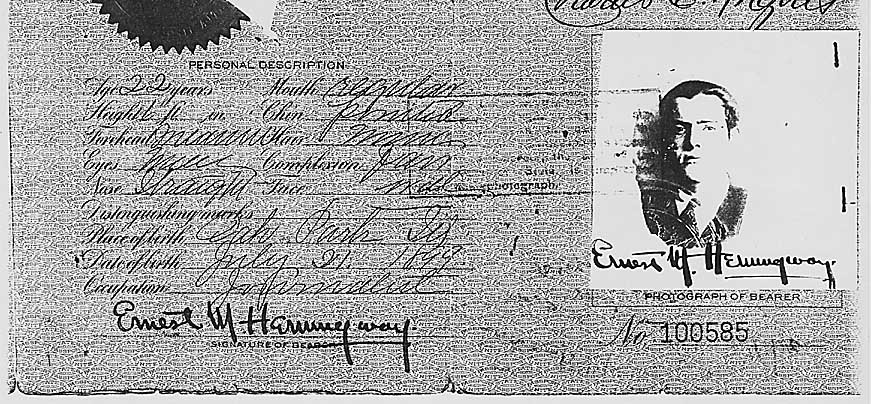

I realized that Brown must have been eviscerated by Hemingway himself. Everything fit, from the prose style to the idiosyncratic orthography. Although I'd never seen a Hemingway holograph before this one, I had seen photographs of his letters in which upper-case E and lower-case e were expressed by a lower-case epsilon or an enlarged version of it. This was consistently true about the E in Ernest and the e in Hemingway in his signature, a facsimile of which was often embossed on his books' covers.

Note the epsilons in Hemingway's signatures on his 1921 passport in the National Archives and Records Administration

This was the period when Hemingway was feeling plagued by a swarm of academic parasites. He was fending off Carlos Baker, Charles Fenton, Philip Young, and other ambitious young scholars writing books about his work. Hemingway was determined to guard his personal life against scrutiny and speculation of the sort that had appalled him in Arthur Mizener’s recent biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Far Side of Paradise (1951).

This was also the period when Hemingway would get dripping drunk and type hate letters into the night. “Criticism is getting all mixed up with a combination of the Junior F.B.I.-men, discards from Freud and Jung, a sort of Columnist peep-hole [sic] and missing laundry list school,” Hemingway fulminated to Meyer in February 1952, just months before he received Leonard Brown’s typescript. “Mizener made money and did some pretty atrocious things . . . with his book on Scott,” he added indignantly, “and every young English professor sees gold in 4 them dirty sheets now. Imagine what they can do with the soiled sheets of four legal beds [Hemingway’s marriages] by the same writer and you can see why their tongues are slavering (this may not be the correct word. If not you please supply it.)”1

Brown was neither a young professor nor a fetishist of dirty laundry. Nor was he known for slavering. Most certainly, his leftist inclinations disqualified him for FBI employment, and he was not and never had been a member of the Communist Party. Aside from whatever modest fee he could expect for his efforts, moreover, any gold to be mined from the book would go to Hemingway and his publisher.

What really ignited Hemingway was likely Brown’s keen interest in Freud and Jung and his application of psychoanalytic theory. Like Shirley Jackson in her seminar paper, Brown did not hesitate to speculate about the author’s inner life.

It is possible that Hemingway intended his diatribe for Meyer’s eyes only, but the typescript was returned to Brown, who surely was mortified by the contempt of his literary idol. He buried his work and thereafter referred to it cryptically as his “lost” Hemingway book.

Brown might have taken some consolation from Stanley Hyman’s searing review of The Hemingway Reader, in which he lamented the self-parodic decay of Hemingway’s talent into egomania, sentimentality, and dogmatism.2

What goes around comes around. The cliché rings true in this case. After I told Jackie about the Hemingway find, I urged her to get the document authenticated and appraised. We consulted a high-end dealer in Syracuse who quickly found a buyer. Jackie collected $5,000.

She had joined the Peace Corps in the sixties and served two years in Africa. She later wrote stories about her experience there, which she now pulled from her file and collected in a privately published book funded by the 5K. Writing well is the best revenge.

1 Selected Letters, 1917-1961, ed. Carlos Baker (New York: Scribner's, 1981), 751.

2 New York Times (13 Sept. 1963). See also Hyman's disparaging review of A Moveable Feast: "Ernest Hemingway with a Knife," New Leader 47 (11 May 1964), 8-9.

John W. Crowley, now retired, taught American literature on the college level for forty-two years. He has published about fifteen scholarly books and a hundred or so essays and reviews.