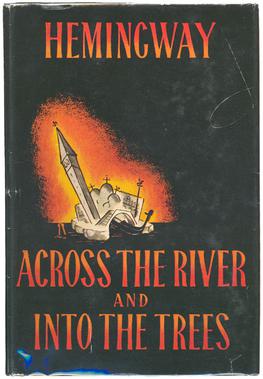

By the early 1950s, Hemingway’s correspondence reveals that he was not at his best physically nor mentally. This period between 1949 and 1950, characterised by Mary V. Dearborn as a “long manic period,”1 culminates in the publication of Across the River and Into the Trees, his literary comeback. Hemingway had in fact not written nor published anything in ten years, his last work being For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). Across the River tells the story of a colonel returning to Venice twenty years after having fought there during WWI, making the novel a comeback story about a comeback.

The writer’s pressure to maintain his reputation when he was writing Across the River and Into the Trees in 1949 and 1950, combined with his unsteady mental and physical state of the time, are visible in his private correspondence.2 The writer expressed feelings of both blind trust and abhorrence in the novel and in his literary talents. Exchanges with editors and friends in 1949, for instance, shows a clouded sense of reality and a very strong literary ego. In separate letters to friends Al Horwits and Ed Hotchner in October 1949, Hemingway compares himself to Shakespeare and mentions that he can supersede the world’s most famous western writer on writing about Venice. He repeatedly affirmed his confidence in the novel in September 1949 to his son John, friend Dos Passos and editor Charles Scribner.

Yet, and especially when finishing the novel, the writer started expressing doubts about it. He wrote to Charles Scribner in October 1949 and asked not to have any big publicity events for the novel. While Hemingway tried to keep a brave face after receiving the first mixed reviews of the novel, letters to his friends and colleagues such as Alfred Rice and Wolfang Klinke, written in August 1950, explain that the novel was not meant to be understood by everyone. In a letter to Mr. Steward written in August 1950, Hemingway also started recognising and mentioning that the physical pain he was in made the novel’s writing process more difficult than any of his previous ones.

Negative reviews, however, affected him. Hemingway personally answered and insulted some authors of negative reviews. In a letter addressed to Cyril Connolly in September 1950, Hemingway makes petty comments on Connolly’s social status, last name, and number of published books.

The correspondence around Across the River and Into the Trees highlights, on one hand, the vulnerable mental and physical state Hemingway was in during the writing and the reception of the novel. On the other hand, these letters also reveal Hemingway’s difficulty in dealing with negative reception at a crucial point of his career. In his moments of clarity, he knew the novel was not in agreement with his readership at the time, but that did not make it easier to accept.

1 Mary V. Dearborn, Ernest Hemingway: A Biography (2017), 522.

2 All of these unpublished letters were reviewed during archival research at the JFK Library in May 2024 and can be bound in Hemingway's outgoing correspondence in boxes OC06, OC07 and IC18.

Laëtitia Nebot-Deneuville is currently a PhD candidate at the School of English of Dublin City University. With a background in English and Italian translation, her research now explores Anglo-American Literary Tourism in Northern Italy in the Twentieth-Century, especially through the fiction of E.M. Forster, Frederick Rolfe, Ernest Hemingway and Edith Wharton. Laëtitia has been awarded research grants from the Irish Association of American Studies, the European Association of American Studies, the Edith Wharton’s Society, and DCU’s School of English, and her research is supported by the Irish Research Council. She previously posted "If Hemingway Had Known Twitter (Now X)" for The Hemingway Review Blog.