This piece grew out of my work on editing The Sun Also Rises for Broadview Press and has become part of a separate project examining four places in the novel that include the terms “nègre” or “négresse” in their names:

· Au Nègre de Toulouse (also called Lavigne’s Restaurant)

· Au Nègre Joyeux

· Biarritz-La Négresse train station

· Chope du Nègre

This is a work in progress; I welcome any insights or information from readers who know about the histories of any of these places.

Some excellent scholarship has focused recently on how racial difference operates in the Paris section of Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (see, for example, Dudley, Holcomb, Lehofer, Miller). Most of this work regarding Black-white racial difference centers on the two Black characters in the novel: the drummer at Zelli’s who is a good friend of Brett’s and the boxer whom Bill encounters in Vienna.

To my knowledge, critics have not explored the racial significance of the four places in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises that feature the words “nègre” or “négresse” in their names. Today these words are as offensive as the “n-word” in English, though some argue they had neutral or positive meanings in 1920s Paris.1

This blog posting is one section of my overall argument that these places circulated problematic images and histories that challenge their supposed positive connotations. While such connotations related to Black life were common in 1920s Paris—with its love of Black art and culture characterized as modernist primitivism (e.g., Pavloska), “negrophilia” (e.g., Archer-Straw), and “Le Tumulte Noir” (“The Black Craze”; e.g., Blake)—a closer look at these places and their iconography reveals the stakes of such arguments, especially for Black African and African American people. Exploring them can thus enhance our understanding of how race functions in the Paris that Jake Barnes inhabits and narrates.

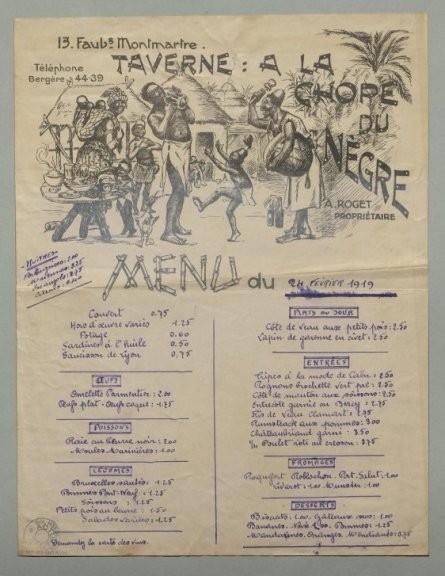

Chope du Nègre was a tavern located at 13, rue du Faubourg-Montmartre in the 9th arrondissement (the Opéra district). While praising the delights of “sportif” France, especially Paris, the bicycle racing team manager whom Jake meets in San Sebastían asks whether he knows Chope du Nègre, suggesting it would be a good place for them to reunite. Jake replies that he knows the place and will see the manager there sometime (257). “Chope” means “mug” or “tankard” as in a mug of beer, so the name translates to “Negro’s Mug” or “Mug of the Negro.” As the historical menu, dated 24 February 1919, in Figure 1 makes clear, the full name of the restaurant was Taverne: A La Chope du Nègre, not Chope de Negre, which is how the Scribner’s edition has it.

The menu of Chope du Nègre features an African man drinking beer from a large mug, with two bottles on the ground and an empty mug on top of one. Additional mugs are bunched together on a table with food, and another bottle lies on the ground under the table, its contents spilling out. The scene is conventionally primitive with the drinker wearing only a loincloth, and an African woman carrying two infants in a large cloth bundle on her back. Another child tries to grab food (apparently a chicken leg) from the table. An adult man wearing a tunic—likely a danshiki (now called dashiki), “a loose-fitting pullover which originated in West Africa as a functional work tunic for men” (Durosomo)—plays a drum. An adolescent boy dances, and another smiles while possibly playing an instrument. No one wears shoes. Their homes are traditional round huts with thatched roofs. A chicken squawks on the ground, contributing to the drunken musical chorus. It is a merry scene filled with stereotypes of grinning Africans consumed by music and alcohol.

Although the menu of Chope du Nègre suggests that patrons could lose their inhibitions and act like the “natives” depicted in the scene, we can assume their experiences were quite different. The “natives” wear stereotypical tribal clothing unlike the sporty or otherwise fashionable clothes of the 1920s Parisian pub patrons.2 It is no coincidence that Jake describes the “two good-looking French girls” hanging out with the bicycle racing team in San Sebastían as having “much Rue du Faubourg-Montmartre chic” (256). This is the same bustling street on which Chope du Nègre was located. Customers like these have money to spend on a night out and might even spend their time following a bicycle racing team or being part of one.3 They live and play in a modern city environment.

Thus, the menu invites customers to have a carefree, unsuppressed time while patronizing the tavern but also erects a racial barrier, implying that although white patrons could act like the “natives,” they would never (want to) be them. No matter how “blind” from drinking they might get, these customers are ultimately not the tribal Africans who drink, dance, and sing on the menu. If African Americans and Black Africans visited the tavern during this time, they might have wondered when they would be free of degrading stereotypes that sustained colonialism and slavery and now were used to advertise places and products.4

Notes

1 Critics such as Stephan Likosky refute the view that “nègre” and “négresse” did not carry the negative meaning in the 1920s that they do today. In With a Weapon and a Grin: Postcard Images of France’s Black African Colonial Troops in WWI, Likosky reprints a card, dated 1919, with a “marraine [godmother]” who is just learning that the soldier with whom she has been corresponding is an African. The Senegalese infantryman confesses to the girl, “Ma jolie Marraine, j’ai un aveu à vous faire... je suis nègre.” The English translation printed on the card reads: “My dear little godmother I must tell you something… I am a nigger,” thus demonstrating an equivalence between the French “nègre” and the English n-word, a word that was “just as derogatory in the early decades of the twentieth century as it is today” (65).

2 For more about sportive fashion for women in France at the time, see Pyper.

3 As the bicycling team manager tells Jake, the number of motor cars in France that now follow the bicyclists from town to town during a road race has increased (257), revealing it to be a sport that attracts the wealthy and those with leisure time.

4 Over 160,000 Black Africans fought and died for France in the trenches of Europe during World War I, which transformed their primary image from people with primitive qualities to individuals who had participated and performed well in battle (Hale 91). However, this positive revision was short-lived or, at the very least, it competed with persistent negative images. Dana S. Hale writes that in the 1920s, “entrepreneurs began to increase their use of comic portrayals of blacks that emphasized stereotypical qualities associated with the ‘race.’ These trademarks evoked the idea that blacks were ignorant and childlike—grands enfants. . . . The growing presence of trademarks such as these indicates that French commercial images of blacks actually became more demeaning in the early twentieth century. The most likely source for these caricatures is American images of blacks in publications, posters, and trademarks for items sold in France” (97).

Works Cited

Archer-Straw, Petrine. Negrophilia: Avant-Garde Paris and Black Culture in the 1920s. Thames and Hudson, 2000.

Blake, Jody. Le Tumulte Noir: Modernist Art and Popular Entertainment in Jazz-Age Paris, 1900-1939. 1999; Pennsylvania State UP, paperback ed., 2003.

Dalton, Karen C.C., and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. “Josephine Baker and Paul Colin: African American Dance Seen Through Parisian Eyes.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 24, no. 4, 1998, pp. 903-34.

Durosomo, Damola. “The Dashiki: The History of a Radical Garment.” okayafrica, 28 May 2017; https://www.okayafrica.com/dashiki-history-african-garment/.

Dudley, Marc K. Hemingway, Race, and Art: Bloodlines and the Color Line. Kent State UP, 2012.

Hale, Dana S. Races on Display: French Representations of Colonized Peoples, 1886-1940. Indiana UP, 2008.

Hemingway, Ernest. The Sun Also Rises. Edited by Debra A. Moddelmog. Broadview P, 2024.

Holcomb, Gary Edward. “A Classroom Approach to Black Presence in The Sun Also Rises.” Teaching Hemingway and Race, edited by Gary Edward Holcomb, Kent State UP, 2018, pp. 105-113.

---. "Hemingway and McKay, Race and Nation." Hemingway and the Black Renaissance, edited by Gary Edward Holcomb and Charles Scruggs. Ohio State UP, 2012, pp. 133-50.

Lehofer, Morgan. “‘Intellectual Evasion’ or ‘The Spirit of Tragedy’? Re-thinking Race in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises.” The Hemingway Review, vol. 43, issue 1, 2023, pp. 52-66.

Likosky, Stephan. With a Weapon and a Grin: Postcard Images of France’s Black African Colonial Troops in WWI. Schiffer, 2017.

Miller, D. Quentin. “‘Injustice Everywhere’: Confronting Race and Racism in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises." The Hemingway Review, vol. 43, issue 1, 2023, pp. 38-51.

Pavloska, Susanna. Modern Primitives: Race and Language in Gertrude Stein, Ernest Hemingway, and Zora Neale Hurston, 2000. Routledge, 2013.

Pyper, Jaclyn. “Style Sportive: Fashion, Sport, and Modernity in France, 1923-1930.” Apparence(s), vol. 7, 2017; https://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1361?lang=en

Debra A. Moddelmog is dean of liberal arts emerita and professor of English emerita at the University of Nevada, Reno. She co-edited Ernest Hemingway in Context with Suzanne del Gizzo and is the author of Reading Desire: In Pursuit of Ernest Hemingway. Her edition of The Sun Also Rises was recently published by Broadview Press. Feedback can be sent to dmoddelmog@unr.edu