It happened one night—at the mall! I was on my knees surrounded by cardboard boxes full of used books. Colleagues and neighbors who volunteered to run the local AAUW annual used book sale had enlisted me. On the last evening, they offered me as many books as I could carry home with me if I sorted out the remainders. Some would go into storage for the next year’s sale and the rest into the dumpster.

Right beside me was a table piled with books, its top just at eye level. Reaching up to examine the next stack of books, my memory was jogged by two words at the top of a faded and frayed book spine: “Beautiful Stories.” No, it couldn’t be Beautiful Stories About Jesus. But I opened it anyway. Yes, yes it was. It was one of the books at Windemere, listed in the back of the 1999 printing of Ernie: Hemingway’s Sister “Sunny” Remembers. I had not been looking for a copy, but there it was. How could a title like that slip from memory? What it sounded like was the period equivalent of a “Golden Book” for children with oversimplified and stripped down happy miracle stories. That was not the case.

The title page is by today’s standards clearly overworked. (See image below.) The full title is Beautiful Stories About Jesus: The Complete Standard Life of Christ. First published by Canon Farrar (1831-1903) D. D., F. R. S. (Doctor of Divinity, Fellow of the Royal Society) in 1874 as The Life of Christ, it was retitled for this 1913 illustrated edition. What “authorized” means I am not sure. The “self-pronouncing” feature involves diacritical spellings of all Biblical names and places in the text—including every textual use of such words and names as Jēʹ-sŭs, Eʹ-gypt, Mâʹr-y, Jō-sĕph, and even my own name—Dāʹ-vĭd, just in case I might have forgotten how to pronounce it—a truly annoying and distracting feature.

The text runs to 723 pages and divides its biography of Christ into 62 “Beautiful Stories.” Not a selection of random happy stories, Farrar presents a comprehensive biography. He naturally derives his narrative from the gospels and epistles but does not shrink from reference to historical sources. He writes as a scholar but for an educated adult audience. The volume lacks notes, a bibliography, and a general index, though it does include an index of the art and artists featured in this particular edition: “Biographies of Great Painters and Index of Great Paintings” (pp. 709-23). I checked the usual online booksellers and located copies available at reasonable prices.

The text runs to 723 pages and divides its biography of Christ into 62 “Beautiful Stories.” Not a selection of random happy stories, Farrar presents a comprehensive biography. He naturally derives his narrative from the gospels and epistles but does not shrink from reference to historical sources. He writes as a scholar but for an educated adult audience. The volume lacks notes, a bibliography, and a general index, though it does include an index of the art and artists featured in this particular edition: “Biographies of Great Painters and Index of Great Paintings” (pp. 709-23). I checked the usual online booksellers and located copies available at reasonable prices.

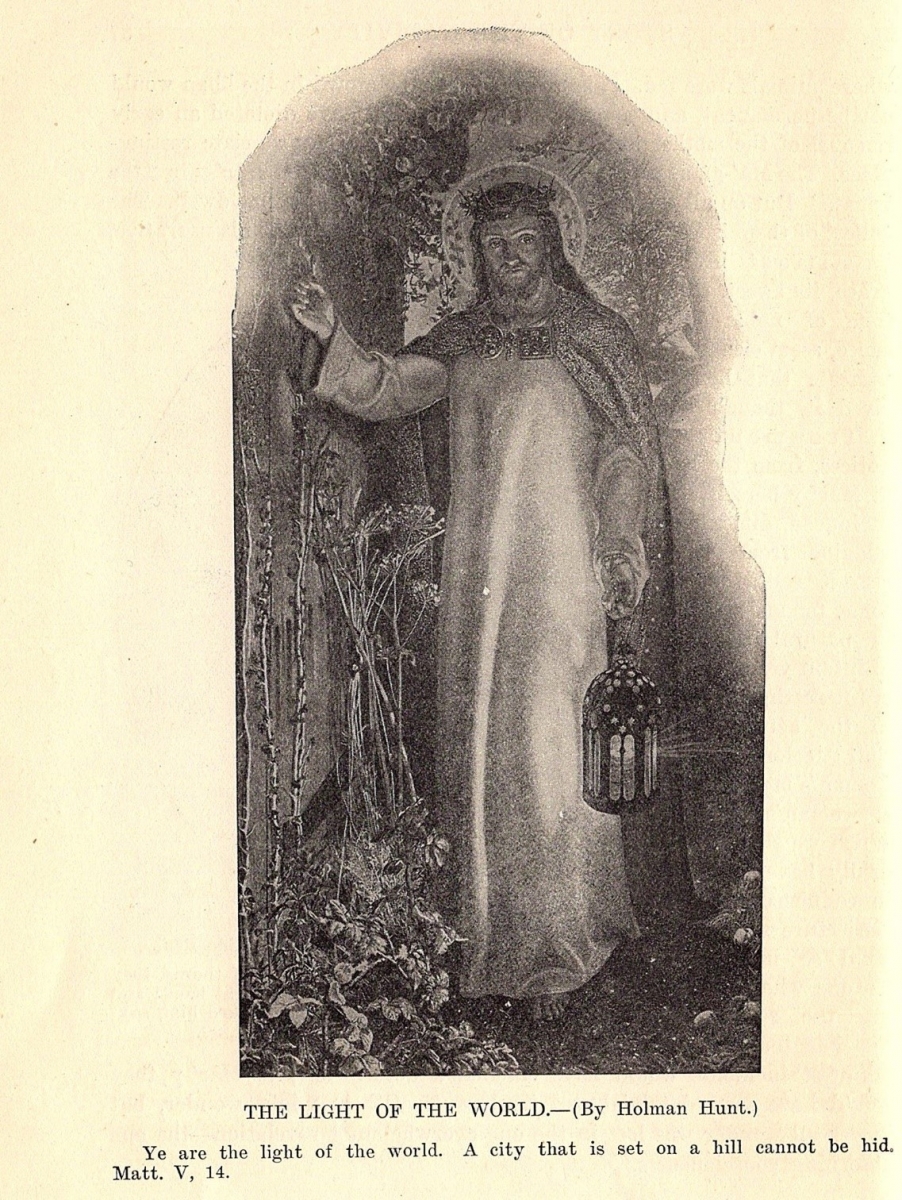

For the Hemingway scholar, the “pictorial-interpretation” feature probably generates the most interest. The volume includes black and white images of paintings, engravings, drawings, etc. by one hundred artists, some renowned, some obscure. The images are not high quality even by standards of the day. Each index entry provides a short sketch of roughly 25 to 75 words about the painter and lists titles and page numbers for each image. Notable artists (with the number of their paintings listed parenthetically) include the following: Michel Angelo (1), Alexandre Bida (41), William Bouguereau (7), Edward Burne-Jones (1), Leonardo da Vinci (3), Andrea del Sarto (1), Gustave Dore (4), William Holman Hunt (3, including “The Light of the World”! See image.), Raphael (11), Peter Paul Rubens (4), Titian (3), and Van Dyck (6). A special section lists the 22 “Madonna and Child” paintings. Bida (1813-1895), touted on the title page, was a recognized nineteenth-century illustrator of narrative biblical and romantic/oriental subjects. He had studied under Delacroix. He certainly did not exemplify the modernism that would ultimately so deeply influence Hemingway’s taste in art as well as his writing. More likely is the possibility that Bida and numerous other of the artists featured in the text would come to represent to Hemingway what the modernists rebelled against.

Not many novelists have shown as heavy an influence of painters on their writings as has Hemingway. The impressionist and modernist painters Hemingway came to love, despite their wide divergence in style and vision, generally shared a love of everyday subject matter rather than the mythological, historical, narrative, and religious subject matter preferred by previous generations of artists. The images presented in Beautiful Stories, especially those by lesser-known artists, tend toward the narrative, the didactic, and even the maudlin. Not surprisingly, Hemingway himself seems to have shown a preference for the expressive rather than the narrative in his choice of art.

Not many novelists have shown as heavy an influence of painters on their writings as has Hemingway. The impressionist and modernist painters Hemingway came to love, despite their wide divergence in style and vision, generally shared a love of everyday subject matter rather than the mythological, historical, narrative, and religious subject matter preferred by previous generations of artists. The images presented in Beautiful Stories, especially those by lesser-known artists, tend toward the narrative, the didactic, and even the maudlin. Not surprisingly, Hemingway himself seems to have shown a preference for the expressive rather than the narrative in his choice of art.

As to the prose of Beautiful Stories, Canon Farrar was a man unable to resist the temptations to moralize or to adopt a defender-of-the-faith tone. For example, of the sellers of livestock and money changers Jesus drove from the temple he writes,

Why did not this multitude of ignorant pilgrims resist? Why did these greedy chafferers content themselves with dark scowls and muttered maledictions . . . ? Because sin is weakness; because there is in the world nothing so abject as a guilty conscience, nothing so invincible as the sweeping tide of a Godlike indignation against all that is base and wrong. How could these paltry sacrilegious buyers and sellers, conscious of wrong-doing, oppose that scathing rebuke, or face the lightnings of those eyes that were enkindled by an outraged holiness? (208-209)

It goes on for four more pages.

At 9” by 6” and 723 pages, Beautiful Stories qualifies as a tome, making it an unlikely volume for Hemingway to have slipped into a pocket to carry on his rambles across lake and forest; nevertheless, one easily imagines his interest in art sparked on a rainy day at Windemere as he leafed through these pages. If he did, he probably ultimately reacted against it, for both the didactic/narrative quality of so many of the paintings and the heavy moralistic tenor of Farrar’s prose.