On Updating The Hemingway Log: A New Conversation with Brewster Chamberlin

Since 2015, Hemingway completists have come to rely on Brewster Chamberlin’s 400-page chronology of Papa’s life, The Hemingway Log: A Chronology of His Life and Times, as the final word in resolving the many conflicting dates and timelines that appear throughout the vast body of scholarship and criticism.

Published by the University Press of Kansas, the compendium of information does for Hemingway what reliable sources such as Jay Leyda’s The Melville Log: A Documentary Life of Herman Melville, 1819-1891 (1951) and Dwight Thomas and David K. Jackson’s The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe, 1809-1849 (1987) have long done for canonical writers: the book serves simultaneously as a handy reference guide and as a “just the facts”-style biography. Unfortunately, both the rise of the Internet and changes in the publishing industry have made these types of projects rarer and rarer, which is another reason that Brewster’s meticulous work is so valuable.

As those who’ve met Brewster well know—perhaps from hanging out with him and his wonderful wife, Lynn-Marie, over wine at their former cigar-roller’s cottage near the cemetery where Bra Saunders and Joe Russell are buried in Key West, as I do most summers—this type of scholarly effort is always evolving. No sooner are chronologies published than new evidence arises and details must be adjusted. Because Brewster has been so essential to helping the Hemingway Letters Project verify information for The Letters of Ernest Hemingway series, the Society decided we would publish his updates to The Hemingway Log as a special PDF “supplement” to The Hemingway Review.

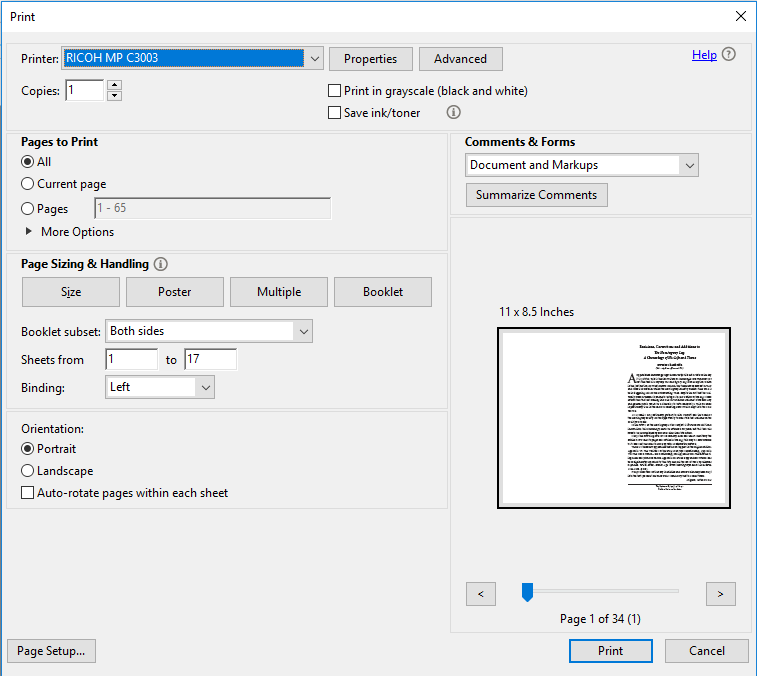

The updates are available for free by clicking HERE. If you would like to print the file and tuck into your copy of The Hemingway Log, all you have to do when you hit print is click the “booklet” option on your menu. The resulting pagination will allow you to simply fold the pages in half and staple down the middle as if you have your own “off-print.”

The conversation that follows updates the interview we conducted with Brewster for The Hemingway Society Newsletter back in 2017. You can read that article HERE.

Many thanks to Brewster for answering these questions!

—Kirk Curnutt

Q: The last time we did an interview for the Hemingway Society’s newsletter The Hemingway Log had just been published. How quickly after the book was in print did you realize that your job wasn’t done, that you were going to continue compiling and correcting the Hemingway chronology?

A: As with all such chronologies, including my own about Lawrence Durrell (2007, revised and expanded edition 2019), the moment it came off the press it was out of date and required corrections, additions, etc. The first notice came from my brother Dean who noticed that the city name Perpignan was spelled Perpignon. Thrice! The other first series of corrections came from Hemingway scholars informing me I had misdated the publication of a magazine or a visit to a friend, those types of corrections which I noted in the revisions version with due credit.

Q: What kind of feedback have you received from Hemingway scholars and fans about The Log?

A: When I began as a part-time volunteer research associate at the Key West Art and Historical Society about 15 years ago I needed a brief timeline of EH’s life on the island to help me catalogue his papers and artifacts at the KWAHS museum and in the Toby and Betty Bruce Collection. As I continued work on the timeline it grew in size and importance and I began sending its additions to Sandra Spanier for the Hemingway Letters Project and to Paul Hendrickson who was working on his book Hemingway’s Boat. Paul praised the chronology in his book, urged that it be published, and made the original connection to the UP Kansas, which Professor Spanier and others supported. Several scholars have praised the Log and noted its usefulness for their own books. No negative reviews as far as I know, for which I am grateful.

Q: Errata are the bane of a writer’s existence. What’s the biggest mistake from the published edition you’ve corrected in this update?

A: Aside from the occasional typos and misspellings not caught in the proof, there were surprisingly few nasty mistakes; for example spelling the poet’s name Paul Laurence Dunbar “Lawrence”; Melville’s Billy Budd was published posthumously in 1924, not 1922; the October 23, 1929 date for EH and a group of friends meeting with Gertrude Stein should have been November 27, 1929; the correct spelling of Maud Cabot Morgan’s name is not Maude; and so on.

Q: I had to chuckle when I saw one of your corrections is to change a reference to “suitcase” to “valise” in reference to the pivotal 1922 incident when Hemingway’s apprentice fiction is stolen from the Gare de Lyon. Were there other moments when you felt you needed to correct a word choice instead of a fact?

I don’t recall making another change of a word in this manner.

Q: A great many of your updates include references to scholarship that’s come out since the publication of The Log, including works by Scott Donaldson, Mary V. Dearborn, Andrew Farah, and many others. Did you read every new Hemingway study to find discrepancies with The Log?

A: As readers will know, the Hemingway industry is massive and continues to grow like Topsy, as it were. Who can keep up with such an extensive spread of publications while at the same time working on other major projects? At my age, 80, I can’t. So I did not read every new piece on EH since the publication of the Log; I skipped the works which dealt with literary criticism and explication but did read the works you mentioned and others.

Q: Which of these works published since 2015 would you say sparked the most additions?

A: In addition to those you mentioned, I made serious use of Nicholas Reynold’s book in which he attempts to show that EH was a spy for the Soviet Union, unsuccessfully in my opinion as I note in a lengthy appendix on the subject (otherwise I have high praise for his research and writing, and he praises the Log); Ashley Oliphant’s book on EH and Bimini; James McGrath’s discussion of EH, Dos Passos, et alia as ambulance drivers in WWI and, more importantly when they actually met; Richard Owens book on EH and Italy which one must read with caution; and others cited in the revisions text.

Q: One character who creeps into the Hemingway story that I guess I’d never realized was involved in it, even marginally, is Samuel Roth (1893-1974), the infamous pornographer/”booklegger”—not to mention virulent anti-Semite—probably best known as the man who pirated Ulysses and Lady Chatterley’s Lover in the US. Tell us what you discovered about Hemingway and Roth.

A: What I discovered from EH’s letters and the literature on James Joyce is explained in the revisions; namely EH was angered by Roth’s PR saying he’d publish EH’s work, without his permission, but never did. EH noted that his anger was about nothing compare to what Roth did with Joyce’s Ulysses, a scandal of the first water.

Q: Some of your additions involve Hemingway only indirectly. I love the new entry in which you cite a letter from Leonard Bernstein’s former roommate, Alfred Eisner, sings the praises of For Whom the Bell Tolls based on reading the galleys, before the novel was published. How did you find this reference? Did you just happen to be reading a Leonard Bernstein biography? Or do you have a magic search engine that combs the Internet for similar bits of information?

A: I happened to be reading the Bernstein letters in which this information appears. I’ve been a fan of Bernstein, his life and work, since I heard (and watched) him conduct the New York Philharmonic at Lewisohn Stadium (no longer extant) in the late 1950s with a Louis Armstrong ensemble and the Dave Brubeck Quartet. What an evening!

Q: This update also includes three new appendices, one on Hemingway as a “spy,” one on the Hemingway-Joyce relationship, and another on Hemingway and Orson Welles. I suspect you could have added three dozen new appendices given how much new information regularly surfaces. Why the Joyce and Welles updates in particular?

A: I began reading Joyce in the 8th grade, believe it or not (along with Mickey Spillane and Faulkner) when in 1953 for some reason I picked up a Signet edition of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and became enraptured. All the rest followed, except, as one might imagine in a non-academic, Finnegans Wake, beyond the first two pages of which I have never advanced, not even the other day when I looked up the exact words of the first sentence for another purpose. I still have the first 1959 edition of Ellmann’s magnificent biography which I absconded with from a Long Island Macy’s branch on Christmas Eve that year in return for the company firing me from my minor position as a clerk on that very eve. I assume the statute of limitations relieves me of any danger of legal prosecution for this heinous crime. I’ve never ceased to read Ulysses and Dubliners or the several Joyce biographies. His life and work fascinate me. So his relationship with EH became gist for my mill, so to say.

Orson Welles: The Museum of Modern Art in NY mounted a retrospective of Welles’s films in 1959 or 1960 ending with Touch of Evil. I attended every showing. That began a 60-year history of what I call serious fandom which has never ceased in intensity, interest and pleasure. His relationship with EH has been either ignored or misinterpreted, much of the blame rests with Welles himself who made up stories over the course of his career (“I was a very good friend of Hemingway’s.”) in various interviews. I think I’ve got the narrative correctly in the appendix.

Q: Another bit of minutiae I love is when you cite a photograph from Getty images to suggest a date for the final meeting of Hemingway and Welles in Paris (2 October 1959). Because Getty can be a little loosey-goosey with dates you add a necessary “if this is correct.…” But do you regularly search the Getty database?

A: No, I don’t. I stumbled upon this image by searching EH and Welles for the appendix.

Q: Are you ever able to sit back and enjoy a Hemingway book, or do discrepancies in dates always leap out at you immediately?

A: I do wish sometimes I could read a book about EH without a critical view, but it is impossible. (In the 1960s I re-read The Sun Also Rises every year; can’t do that now; no time.) Again, I stay away from the purely academic analyses and explications of his writing which could not enter into the Log without bursting its integument. Two exceptions, however, are Carlos Baker’s EH as Artist and your book, Kirk, on To Have and Have Not.

Q: Finally, I notice in your introduction you say, “This chronology could be extended for years, but that task will have to be accomplished by someone other than this author.” Surely you don’t think you can retire from your job as the Keeper of the Hemingway Chronology?

A: I fear I must. A revised and expanded edition of what is now called The Lawrence Durrell Log: A Chronology of His Life and Times (yes, I know, I know!), originally published in Greece in 2007 was published in London in the spring of 2019 and I must still attend to that, and there are at least three other writing projects demanding attention, most especially the fourth and final volume of the novel The Berlin Book (Ursula’s Triumph or The End of the Beginning), and then there’s the next (and final?) novel, “Twentieth Century Limited” for which only notes and brief passages exist.

Enough, n’est-ce pas.

So goodnight, Mrs. Calabash, wherever you are.