Today’s writers may call upon artificial intelligence and other tools to enhance their craft. For his, Ernest Hemingway sometimes used a device he gave the otherworldly name “devil box.”

Readers of Valerie Hemingway and Mary Dearborn have seen references to this “devil box,” a tape recorder used between Hemingway and his friend and collaborator A.E. Hotchner in Spain in 1959. Before Hotchner’s travel from New York to Europe that summer, Hemingway had asked Hotchner to procure a few items for him, mindful of their size and weight and potential baggage fees to be incurred, including the “smallest practical” tape recorder.1

Both Valerie Hemingway and Dearborn note that Hemingway had developed a phobia about publicity and specifically about being recorded.2 Cuadrilla member Valerie Hemingway believed Hotchner’s clown act allowed him to get away with possessing a tape recorder in the Hemingways’ presence. The freckled “El Pecas” Hotchner was full of inside jokes and sometimes played the buffoon. Valerie writes “a tape recorder on anyone else would have been traitorous; with Hotch it was a cause for amusement, the harmless ‘devil box.’ ”3

Dearborn explains that Hotchner and Hemingway worked on updates to the television production of "The Killers" by exchanging “Mohawk tapes,” and although Hemingway was not comfortable with the machine, it was handy at a point when he was finding it difficult to write.4 “The Killers” was to be the first of several Hemingway stories in a series of televised plays Hotchner was producing. From New York in September 1959, on behalf of CBS television network, Hotchner asked Hemingway if he would “speak onto one of your Mohawk tapes a sentence or two about THE KILLERS,” such as where it was written or what motivated it, and have Mary Hemingway deliver the tape on her arrival.5 Hemingway gave several reasons for saying no: he was in Paris while the “box” was in Málaga, they would not be compensated for this extra work, and he would have wanted Hotchner to be there to advise him and review any recording.6

Hemingway’s so-called “devil box” was an early portable tape recorder produced by Mohawk Business Machines. The Museum of Obsolete Media describes a Midgetape 44 model recorder introduced by the Mohawk company in 1955; the price was about $250. This device used a tape cassette with a quarter-inch tape which allowed for 30 or 45 minutes of recording on each side. It came with a microphone and headphone jack, and had adaptors for recording telephone conversations, a wristwatch microphone and a leather bag with hidden microphone.7 To what extent Hotchner may have employed the cloak and dagger adaptors is not clear, but Dearborn judges from Hotchner’s later Papa Hemingway memoir that he did plenty of tape recording that summer.8 In Hemingway in Love, Hotchner specifies using a Midgetape to record conversations and augment his written notes.9

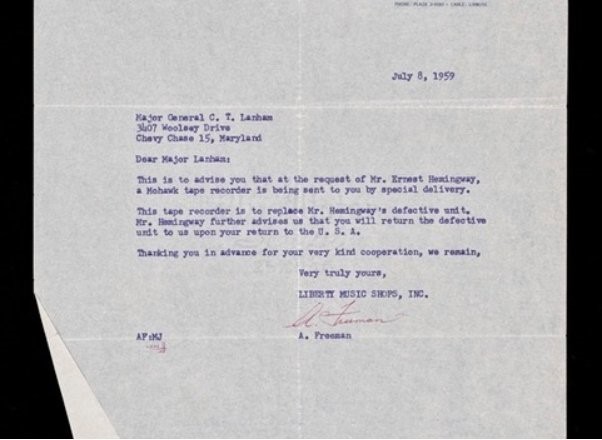

Evidently Hemingway found his recording device useful, as he arranged for General Buck Lanham, dear friend and guest at his elaborate 60th birthday celebration in Spain, to hand-carry the defective “devil box” back to the U.S. and exchange it for a new one.

Lanham related to Hemingway the going-over he received from U.S. Customs when he arrived with the curious device at New York’s Idlewild airport. Inspectors examined the machine and asked Lanham how it worked, the incoming passenger line stacking up behind him as officials rifled through dirty laundry and the volume of Great Modern Short Stories in his bag. In the same letter, Lanham extends wishes to Hemingway that his alliance with Hotchner thrive and prosper, adding a cautionary note about business deals between friends, although Lanham does not believe Hotchner is a “fast buck guy” any more than Hemingway is.10

As seen in the letter from Liberty Music Shops below,11 Hemingway had a new tape recorder sent “special delivery” to Lanham’s home in Chevy Chase, Maryland to replace the defective unit. Whether Hemingway used the device to record his words in the two years to follow is for others to discover.

Photograph of a 1959 letter to General Buck Lanham from Liberty Musical Shops, reprinted courtesy of Princeton University Libraries

Greer Rising and Eileen Martin are working on a book based on letters from Buck and Pete Lanham to Greer’s family that will explore the friendship between Lanham and Hemingway.

1 Albert J. DeFazio III, ed., Dear Papa, Dear Hotch: The Correspondence of Ernest Hemingway and A.E. Hotchner (Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 2005), 256-257.

2 Mary V. Dearborn, Ernest Hemingway: A Biography (New York: Vintage Books, 2017), 597.

3 Valerie Hemingway, Running With the Bulls: My Years with the Hemingways (New York: Ballantine Books, 2004), 45-46.

4 Dearborn, 604.

5 DeFazio, 269.

6 DeFazio, 270-71.

7 Museum of Obsolete Media, obsoletemedia.org

8 Dearborn, 597.

9 A.E. Hotchner, Hemingway in Love: His Own Story (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015), xvii.

10 Hemingway, Ernest: from Lanham, Charles T., August 6, 1959, Princeton University Library.

11 Hemingway, Ernest: from Lanham, Charles T., Letter from Liberty Music Shops Inc. to Lanham, July 8, 1959, Princeton University Library.